A long hedge is a type of hedging strategy that producers or manufacturers use to lower the risk of price fluctuations. A producer or manufacturer uses such a strategy to lock the price of a commodity or input that they wish to buy in the future. We can also call this hedge as input hedge or a buy hedge, or a purchaser hedge.

Basically, it is a futures contract where the buyer intends to take the delivery of the underlying commodity. In this strategy, the buyer takes a long futures position. If the rate of the underlying commodity goes up, the futures position offsets the increase in the price. Basically, such a strategy helps the manufacturers or producers to stabilize their input or commodity price.

An example will give us a better understanding of this Long hedging concept.

Suppose Company A manufacturers phones. Chips are one of the key input items of a smartphone. And suppose the prevailing market price of a chip is $100. Company A has got a big order that it needs to deliver in six months from now. The firm anticipates the chip prices to move up in the future.

Thus, to reduce the risk of chip price rising, Company A buys a six-month future that is available at $90. In this case, Company A would benefit if the spot price of chips after six months is more than $90. On the other hand, if the spot price after six months is less than $90, then the buyer would only lose the cost of entering the futures transaction. The premium is paid while entering the long futures contract for chips.

A point to note is that a producer can use the hedge to cover some part or all of the risk. The percentage of risk that an investor covers could be represented by the hedge ratio. For instance, if, in the above example, Company A covers one-fourth of the big order, then the hedge ratio is 25%.

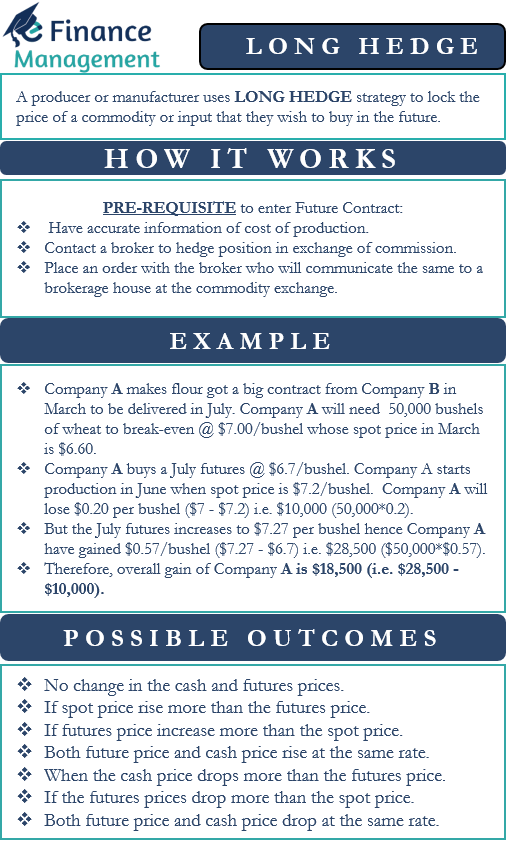

Long Hedge – How it Works?

In simple words, we can say that a long hedge is a strategy that a company uses to control its costs. Such a strategy is effective if a company knows that it will need a particular input or commodity in the near future. So there needs to be clarity with regard to the item, quantity of that item, time horizon, and the rising price outlook. When all these are clearly spelled out, then only the company can take a futures position to offset or mitigate the price rise risk.

Executing this hedge is very simple. All that a buyer needs to do is take a long futures position. Such a position means that the buyer expects the rate of the commodity to rise to go ahead. Now, if the price goes up, the profit from the futures position would help the buyer to offset the rise in commodity prices.

Once you are ready to go for a futures contract, you need to contact a broker with all the relevant information who will assist in hedging your position in exchange for a commission.

Also Read: Cross Hedge

After you place an order with the broker, they will communicate the order to a brokerage house at the commodity exchange.

Example of Long Hedge

Let’s consider another example (this time a bit complex) to understand how the long hedge actually works.

Suppose Company A makes flour, and it has got a big supply contract from Company B. The delivery is in July, while the two entered the contract in March.

Company A estimates that to meet the contract, it will have to start manufacturing in June, and it needs 50,000 bushels of wheat. Further, Company A estimates that to break even, it will have to buy wheat at $7.00 per bushel.

In March, the spot price per bushel was $6.60. Company A, however, expects the price to move significantly in June, i.e., when it starts manufacturing. Thus, to reduce the risk, Company A enters a long hedge and buys a July future, which is trading at 6.70 per bushel.

A single futures contract covers 5000 bushels. So, to cover the full contract, Company A will need to buy 10 futures contracts (5000*10= 50,000)

Now, suppose in June, when Company A starts production, the spot price of what is $7.20 per bushel. Similarly, the price of July futures also increases and is at $7.27 per bushel.

Since the actual purchase price is $7.20 per bushel, Company A will lose $0.20 per bushel (the break-even price was $7 per bushel). So, the total loss for 50,000 bushels will be $10,000. This means the Company will incur a loss of $10,000 in the supply contract with Company B.

However, Company A has a futures position as well. The July futures have gained and are worth $7.27 per bushel in June. This means Company A would gain $0.57 per bushel ($7.27 per bushel Less $6.70 )

So, the total gain for 50,000 bushels will be $28,500 ($0.57 * 50,000).

Now, the net profit for Company A will be = Total profit in futures transaction Less Total loss in the supply contract.

or $28,500 – $10,000 = $18,500.

This means Company A made a profit even though the price of wheat increased significantly.

Possible Outcomes

A point to note is that there are seven possible outcomes when dealing with a spot and future price. These seven scenarios are:

- When there is no change in the cash and futures prices during the hedge period.

- The spot price could increase more than its futures contract price.

- Or the futures contract price increase may be more than the increase in the spot price of the commodity.

- Both future prices and cash prices rise at the same rate.

- The sports price drops more than the price of its futures contract.

- Or when the futures contract price drops more than the sports price of the commodity.

- Both future prices and cash prices drop at the same rate.

Generally, the cash and futures markets move in the same direction. So, we have not taken the scenarios in which the cash and futures markets go in the opposite direction.

The payoff in all the above seven scenarios will be different. One easy way to get an idea of the payoff in each scenario is to look at the basis. The genesis of all these transactions is the difference between the prevailing cash price and the futures contract price of the commodity at the time of expiry.

For instance, in the above example, the basis in March was 0.10 ($6.60 Less $6.70). In June, however, this basis comes down to 0.07 ($7.20 Less $7.27). Since the basis was less in June, the futures weren’t able to offset the full rise in price.

Generally, the basis in all the above scenarios is usually different, resulting in a different payout. So, it is important for the hedgers to closely track this basis when entering or even after the hedge. This will assist them in taking positions accordingly.

Final Words

We can see a long hedge is a type of insurance. Though they come with a cost, they ensure peace of mind, as well as save a large amount of money at times of unfavorable conditions.